Yap

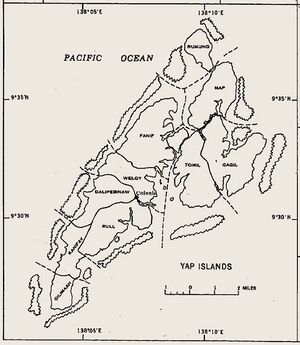

Yap is a group of four main islands and a dozen islets, separated by narrow channels, surrounded by a broad, fringing platform reef.

Alternative spellings and historic names include: Waab, Wa'ab

Yap is a cluster of high islands located at 9° 30' N, 138° 08' E, 60 miles north-northeast of Ngulu and 85 miles west-southwest of Ulithi. The group is composed of four large and ten small islnds completely surrounded by a coral reef which extends nearly a mile offshore and has several openings. Yap as a whole has a length of 16 miles (NE-SW), and a maxim breadth of six miles, and a total area of approximately 83 square miles.

Yap was discovered by Portuguese explorer Diogo da Rocha in 1526; visited by Álvaro de Saavedra in 1528 and Ruy López de Villalobos in 1543; rediscovered by Spaniard Francisco Lazeano in 1686, who called the island Carolina, whence the name of the archipelago; and visited by Bernardo de Egui in 1712.

Yap is a part of eponymous Yap State within Federated States of Micronesia.

Subunits

Atolls and islands within the group include: Marbaa' (Yap Proper), Gagil-Tamil, Rumung, and Maap.

"Yap" is also used as a term for a specific island (Marbaa') as well as the State as a whole. As with many placenames in Micronesia, this is a geographic 'pars pro toto', in which the name of a constitutive village, island or atoll is often used describe the larger island, atoll or island grouping in which it is the predominate member.

Population, Language and Religion

The 2010 FSM Census reported a population of 7,371. Yapese is the spoken language and religious affiliation is primarily Roman Catholic, with a minority of Protestants.

A 1935 count of the population by the Japanese identified 3,713 native residents, 392 Japanese nationals, and eleven foreigners. After the war, in summer of 1946, the US Naval Military Government counted 3,030 local residents on Yap.

Governance

Spain laid claim to the Carolines from the time of initial discovery in the early 1500's but made no attempt to occupy or administer them. In 1885 a Governor for the Carolines was appointed by the Governor General of the Philippines and presence established in Pohnpei and Yap. In this Spanish Period (1521-1899), Yap fell within the Western District of the Spanish East Indies.

After the Spanish-American War, Spain sold the Palau, Caroline, and Marianas Islands to Germany in 1899. In this German Period (1899-1914), the Caroline, Palau and Mariana Islands (excluding Guam), along with the Marshalls, annexed in 1885, were titled Imperial German Pacific Protectorates. The Carolines become an administrative district of German New Guinea under direction of a vice-governor and Yapfell within the Western Caroline District.

The Carolines were seized from the Germans by the Japanese early in World War I. Despite protests from the United States, including the Yap Crisis, the Islands were in 1920 mandated to Japan by the League of Nations. In this Japanese Period (1914-1941), Yap fell within the Yap District of the “Nan'yō Cho” or South Seas Government.

Following liberation of the islands in the War in the Pacific, the islands were administered by the US Navy. The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) was formalized by United Nations Security Council Resolution 21 in 1947. The Navy passed governing duties to the Department of the Interior in 1951. During the USN Period (1945-1947) and the TTPI Period (1947-1979) Yap fell within the Yap Administrative Unit and then the Yap District.

The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) was established with the end of the Trust Territory. The FSM is one of three “Freely Associated States,” or “FAS” nations that entered into a Compact of Free Association or “COFA” with the US. The treaty and agreements provide economic assistance to the countries, secured US defense rights and set defense responsibilities, and allow FAS citizens to migrate to the United States.

Traditional Culture

Pre-Contact

Yap was part of the Tabinaw, or Yap Land Title and Kinship System (sometimes called the "Yapese Caste" system.

Pre-contact social order was characterized by: a social hierarchy with stronger chiefs where violence used to seize and maintain power (Goldman Level 2 of 3); occasional interpersonal violence (between individuals who frequently, but not always, are known to one another); one or just a few deaths per year (2 on Younger's 0-4 scale); chronic warfare, defined as armed aggression between political communities or alliances of political communities, essentially continuously (4 on Younger's 0-4 scale).

Property rights were characterized by: a land tenure system based on patrilineal ownership (Sudo, Type 4). Food resources are owned by the agnatic (patrilineal) lineage and inherited patrilineally.; a system of sea tenure in which the reef-lagoon is owned by families (Sudo Type 4).

Historically, village chiefs had little judicial authority and paramount chiefs exercised their judicial authority only in the rare cases when a complaint was made to them. Crimes like murder, assault, theft, and adultery were punished in the main by private retaliation on the part of the injured person and his relatives. If the offender was a member of the same settlement, the injured party might forego his right to an eye for an eye and distrain the offender’s land or canoe. He simply placed a coconut frond on the land or beside the canoe, and the property could not be used until compensation had been agreed upon and paid. If the offender was from another village, however, blood vengeance was sought. The family of the victim slew the culprit if they could find him; otherwise one of his kins men. Because of the effectiveness of this system of self-help, sorcery was used but infrequently as ameans of punishment. However, it was often used to discover the culprit or to pile up evidence against him.

Evolution

The Spanish administration contented itself with maintaining a strong garrison on Yap after 1885, and had little effect on the native political institutions.

The Germans, after assuming sovereignty over the islands in 1899, put an end to native warfare and deprived the native chiefs of the power to impose the death penalty, but they adapted their administration to the local governmental organization. They assembled the eight paramount chiefs of Yap once a month at the administrative headquarters to transmit orders and instructions, but they left most matters, including policing, in the hands of the chiefs. Their principal difficulty was in getting roads built. The chiefs, being quite content with the existing native trails, were lax in carrying out orders. Fines proved ineffective because of the excessive cost of collecting and transporting the heavy stone money, which was the only medium in which they could be paid. The problem was finally solved by taking advantage of the native custom of transferring title

Starting in 1914, the Japanese administration further curtailed the power of the chiefs, and sought consciously to minimize the old class differences, but it adhered closely to the local political structure in the selection of native officials. At the same time, an attempt has been made to replace the system of private retaliation by empowering the paramount chiefs to handle minor offenses.

Present Day

Traditional chiefly authority is exercised by the Council of Pilung.

In Yap, traditional leaders have a role in governnance that enshrines them as a "Fourth Branch." As John Haglelgam, former President of the FSM observed in his "Traditional Leaders and Governance in Micronesia" (1998), “in Yap, the traditional leaders have formal roles in the government. The Yap state constitution created two councils of chiefs: one for the main islands of Yap and one for the outer island chiefs. These councils are empowered to review and disapprove an act of the state legislature if it violates custom and tradition… The legislature cannot override the veto of these councils but can incorporate their objection in the bill and return it for their review. So far. the councils have used their power sparingly. The councils have also expanded their power to review policy of the executive branch which has forced the governor and his cabinet to justify their policy to the councils… The two councils are in essence public watchdogs, making sure that elected officials and bureaucrats are doing their job.“

Cultural Persistence & Distinctiveness

American anthropologists, working to support development of US administration in the wake of the War in the Pacific, examined Yapese culture in great depth, with a particular eye toward understanding the Germans’ and Japanese’ failure to effect social, political and economic change during their rule.

Among their observations, published in the Handbook of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1948, were:

“The character structure of Yap society is distinctive ...Yap possesses a unique social organization, its people differ sharply in personality and outlook from the other island peoples .... Many of the major errors made by Japanese officials in Yap stem from misconceptions of Yap psychology and cultural values. This not only reduced the government to a level of near impotency, but also aroused in Yap sharp opposition which sought to counteract every measure introduced, regardless of its intrinsic merit.”

“Acculturation has hardly touched Yap life. Yapese society does not have, at this point [1948], a fixed set of goals (for modern adjustment) ... So much Yapese thought and effort in the Japanese period was channelized into counteracting the imposed patterns that little positive planning for the future was engaged in, and few changes took place in the social structure...Spontaneous emulation of the foreigner’s ways seldom occurs.”

“The culture of the Yap people is an integrated and effective one. Although certain changes have occurred as a result of contact with European and Asiatic cultures, these changes do not seem greatly to have affected the total configuration of Yap culture. It can safely be said that were all foreign peoples to leave Yap immediately, the pattern of life of the Yap people would hardly be affected.”

“The Yap people “bow down” to no one ... They are an independent people—submitting overtly to force when confronted by it, but not afraid to die for their convictions ...There is no overwhelming awe of the government official or profound admiration of the culture he represents ... The people are not obsequious nor do they have a sense of inferiority in relationships with the dominant group ... Spontaneous emulation of the foreigner’s way seldom occurs .. The Yap personality structure does not make for ease of informal personal relations.”

“In interaction with strangers, Yap people are unaggressive—this must not be equated with hostility or indifference. Ingrained habits call for waiting to see as fully as possible how the outsider is going to act in any possible contingency ... (But) if confronted by an order which overrides a point of view which they hold firmly, they will not execute it regardless of the consequences.”

“Yapese people do not have a brittle personality. They are not explosive, quick to anger or affection … outwardly demonstrative ... The overt expression of emotions is carefully suppressed, and a casual demeanor is universal ...They are deeply concerned that their rulers may understand their modes of thought and action, but feel incapable of making this concern known. Hence, Yap people are highly sensitive to the reactions of their officials and worry over the likelihood of being misunderstood.”

See also Political Status of Yap, Yap's Council of Pilung, and the Tabinaw Caste System of Yap.

Spanish Era

in 1886, the Spanish dispatched nine priests and monks of the Capuchin order to found missions on Yap and Palau, and established on Yap a government office for the administration of the western Carolines.

Mssionary endeavor, though modest, was the principal activity of the Spaniards throughout the period of their rule. They interfered very little in local affairs, and from what little effort they expended they reaped no economic rewards, for the trade of the area was monopolized by Germans, Americans, and Japanese. Their hold over the region remained tenuous and her influence small.

German Era

At the start of the German Period administrative headquarters for the Western Carolines were established on Yap. Here they erected a new administrative building, established a hospital with a resident physician, who soon began to train native assistants and make tours of the other islands, and set up a police force composed first of Malays but soon of trained natives. The system of native administration was completely patriarchal, the Germans interfering as little as possible with local political and social traditions. Six paramount chiefs on Yap were confirmed in office and were made responsible, with the help of their assistant chiefs, for the administration of local affairs. The district officer met with the chiefs once a month, discussed problems, and explained policy; the paramount chiefs then met with their subordinates and gave them instructions.

The German handover of Yap from Spain occurred on 3 November 1899. Germany’s rule in Yap was part of a broader colonial project characterized by strategic assertion, economic extraction, and cultural transformation. While officials often expressed respect for certain indigenous traits, their ultimate goal was to integrate Yap into the German imperial order—efficiently governed, economically useful, and ideologically aligned with Western norms.

The Germans worked conscientiously for the improvement of the area. They built roads, and worked out an ingenious way of making fines payable in native stone money. They encouraged the expansion of the missionary activity carried on by the German Capuchin order. They sent officials and scientists to the various islands to report on local conditions, to prepare improved maps and charts, and to explore economic possibilities. Only in the promotion of trade, which was atter all the primary concern of the administration, did the district officers on occasion resort to dictatorial steps. Native chiefs were required their have their people increase the acreage planted to coconut, to maintain the groves in good condition, and to give a regular accounting to the authorities.

Godeffroy and Sons, a Hamburg firm which had been active in Samoa, opened a branch on Yap in 1869. Hernsheim and Company, also of Hamburg, established trading stations on Palau, Woleai, and Yap in 1873, and later took over the Godeffroy interests. The Deutsche Handels und Flantagengesellschaft, the largest German firm in the Pacific trade, also entered the Western Carolines, and in 1885 was operating stations at Falau, Ulithi, and Yap. In 1887 the leading German mercantile firms amalgamated to form the powerful Jaluit Company, which maintained a station on Yap.

During the German regime Yap was made the center of a submarine cable system for the islands. A cable station was built at Tomil Bay and lines were laid to Guam, Menado in Celebes, and Shanghai. During World War I these cables were cut and the cable station was destroyed.

Japanese Era

The Japanese occupation of Yap began in October 1914, following Japan’s declaration of war on Germany during World War I. Yap, along with other German-held islands in Micronesia, was swiftly taken over by Japanese naval forces without significant resistance, as Germany had limited military presence in the region. Yap held great strategic value because of its position in the western Pacific and the presence of an important undersea telegraph cable station, which connected Germany with its colonies and with East Asia. One of Japan’s immediate priorities was to seize control of this cable station, which they quickly accomplished.

The Japanese occupation was a direct result of Japan declaring war on Germany in August 1914, under its alliance with Britain. By October 1914, Japanese naval forces had seized control of the Marianas, Caroline, and Marshall Islands, which included Yap. The Japanese military acted swiftly and encountered no German military resistance, as the German presence was small and largely administrative. The capture of the islands was carried out with naval superiority and minimal force.

Japan’s principal motivation was strategic control of Pacific territories, especially the telegraph cable station on Yap, which was crucial for communications between German colonies and Europe/Asia. Seizing this infrastructure gave Japan a significant advantage in Pacific intelligence and communication. Although Japan took military control in 1914, the long-term political status of these islands remained unclear until the League of Nations formalized Japan’s mandate in 1920. In the meantime, the occupation was technically unofficial but fully enforced.

Colonia, or formerly "Yap Town or Town of Yap," became the seat of the Yap Branch Government, a section of the South Seas Government based in Koror on Palau, during the Japanese Period.

Under the Japanese administration, the Tomil Bay cable station was rebuilt, and the former Yap-Shanghai line was repaired northward from Yap as far as Naha in the Ryukyu Islands, where a station was erected and a cable connection thus effected between the mandated islands and Japan proper. The government began supplying electricity to the public in 1925.

The police force in Yap consisted of an assistant police lieutenant, Japanese policemen, and native constables, headed by a police lieutenant. There were substations on the island of Maap and Rull. The Japanese established a hospital on Yap with a government physician, as well as a post office, handling parcel post, money orders, and postal savings. the post offices transmitted telegrams by wireless. Yap was the site of a leper asylum, and host to a sub-committee of the Japanese Red Cross, based in Korror.

The South Seas Government established branch meteorological observatory on Yap (position: 9° 30' N, 138° 08, E; elevation 96 feet). Major typhoons hit Yap in 1918, 1920 and 1925. A government-owned radio station with the call letters JRZ was located on the west side of Tomil Harbor. Its facilities included two straight masts about 150 feet high and two short stick masts. The station broadcasted on wave lengths of 300, 600, 1,200 and 1,800 meters, and had a daytime range of about 500 miles and a nighttime range of about 1,000 miles. Another station assumed to be for naval operations had a 50kw set.

Three public school were established on Yap and a boarding houses was maintained in connection with each: the Yap, Maki, and Nifu Public Schools. Students coming from a distance were provided with free lodging and with food. The Japanese language was the main subject of study in the public schools as in the elementary schools; to it were devoted 12 of the scheduled 23-29 instructional hours per week in the regular course, and 10 of the 28-30 hours in the supplementary course. Pupils were drilled in easy conversation e announced policy of the South Seas Government in the teaching of all subjects was to adapt the material to local conditions and to make the courses concrete and practical.

The Japanese government claimed that in the Yap district individual ownership of land remained customary, and 99 per cent of the land was still owned by natives.

War in the Pacific

Rumors of war gradually began to spread among the Yapese in the late 1930’s as the Japanese armed forces started to fortify the island. Guns were tunneled into hillsides overlooking Waneday (Tomil) Harbor. Work started on two airfields located on both the northern and southern portion of Yap. Individual Yapese were at times forced into labor gangs to work on airfields and other military projects. Labor gangs included elementary students and old men considered by most Yapese too old to keep up with the heavy work and pressure. Discipline was severe; some Yapese who were forced to work in some of these projects later told stories of beatings handed out to those who failed to obey an order or were notable to complete the heavy load of work assigned to them. Yapese valuable stone money (Rai Stones) was smashed to pieces as punishment for those who were disobedient to the Japanese. These smashed pieces of stone money were sometimes used as road fill. Old meeting and men houses were torn by the soldiers for firewood.

In either 1941 or 1942 the Japanese built a lighthouse in Gagil and intensive gardening begin shortly there after across a large part of southern Yap.

Yap was not invaded by the American forces. Still, the American forces managed to occupy Yap's neighboring islands of Ulithi, Fais and Ngulu. Daily raids by American planes continued for three consecutive years. For decades after the war, individual Yapese recounted fleeing for safety to places that varied from mangrove muds and taro patches to hidden fox-holes in nearby hills. Air raids were concentrated mostly on the District Center of Colonia, as well as airfield and military facilities. The Americans occupied Yap without opposition after September 2,1945, at which time the Japanese finally surrendered in the Pacific. The US Navy administered the island until 1951 when the Department of Interior took over.

TTPI Period

As the US agency designated to oversee the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, the US Interior Department took over the island from the US Navy on June 21st, 1952. King W. Chapman was named Yap's first civilian district administrator. In 1965 the first general election was held in Yap, in which voters selected representative for the Congress of Micronesia. Three years later, in 1968, the Yap District Legislature was organized. The body consisted of 12 representatives from Yap proper and eight from the Neighboring Islands. Legislators were elected for two-year terms.

Political Status of Yap

Over several centuries, Yap and its outer islands have been administratively group by foreign powers into political units with other more distant islands in Palau, eastern Caroline, and Marshall Islands. Despite this, the People of Yap have always retained very distinctive and cohesive linguistic, social and cultural patterns and identity. At the close of the US administered Trust Territory, elected leaders and the voters of Yap opted to join the nascent Federated States of Micronesia and enter into Free Association with the United States. Still, questions about Yap's Political Status remain unresolved in the minds of many voters and political leaders.

Electoral Divisions

The legislative branch of the Federated States of Micronesia is unicameral. Two types of Senators are elected: at-large senators, one for each of the four states, who serve four-year terms, and population-based senators, representing specific constituencies, who serve two-year terms. The President of Micronesia is elected by the Congress from amongst the four at-large senators, after which a special election is held to (re)fill that seat. Yap is represented in the FSM Congress by the Yap, At-Large Seat Senator, and the Yap, Sole Population-Based District Senator.

Since the establishment of the FSM, Yap State voters have elected and maintained in Congress one Yapese Senator and one Outer Island Senator. This de facto power-sharing arrangement is similar to the requirement in the Yap's State Constitution stating "if the Governor is a resident of Yap Islands Proper, the Lieutenant Governor shall be a resident of the Outer Islands, and if the Governor is a resident of the Outer Islands, the Lieutenant Governor shall be a resident of Yap Islands Proper."

Education

The Local Education Agency, or “school district” for Yap is the Yap State Department of Education and Yap falls within the Waab Zone.

Runway

Yap International Airport (YAP) is located in the southern part of the Yap Islands, also called Wa'ab, a group for four continental islands connected by a single reef. The airport receives regular commercial flights from Guam and Palau. Pacific Missionary Aviation makes trips to the outer island airfields of Ulithi & Fais. The runway is 6,000 by 150 feet of asphalt.

Analysis

Yap is a society of stubborn continuity, where foreign powers have come and gone, each believing themselves agents of progress, and each finding themselves politely resisted or quietly ignored.

The Spanish prayed, the Germans paved, the Japanese policed, and the Americans surveyed—but Yap endured. Traditional chiefs still hold constitutional power as a “Fourth Branch” of government, capable of vetoing laws that violate custom, but the role of cultural continuity runs much deeper than those who are seen by outsiders to embody or lead it. Stone money still sits as silent proof of Yapese permanence.

Anthropologists sent to decode this cultural citadel left mostly impressed: Yapese society, they noted, neither emulates nor assimilates. Its people bow to no one, adopt slowly, and remember everything.

Texts Dealing with Yap

Acord, Suzanne A. ‘Postcolonial Transformation in Yap: Tradition, Ballot Boxes and a Constitution’. University of Hawaii, 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/20843.

Berg, M. L. ‘Yapese Politics, Yapese Money and the Sawei Tribute Network Before World War I’. The Journal of Pacific History 27, no. 2 (November 1992): 150–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223349208572704.

Butler, Janet B. ‘East Meets West: Desperately Seeking David Dean O’keefe from Savannah to Yap’. Georgia Southern University, 2001. http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd_legacy.

Cora, Lee C. ‘Stone Money of Yap: A Numismatic Survey’. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, no. 23 (1975): 1–75. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00810258.23.1.

Gentle, Paul F. ‘Stone Money of Yap as an Early Form of Money in the Economic Sense’. Financial Markets, Institutions and Risks 5, no. 2 (2021): 114–19. https://doi.org/10.21272/fmir.5(2).114-119.2021.

Gregory, Charles Noble. ‘The Treaty as to Yap and the Mandated North Pacific Islands’. American Journal of International Law 16, no. 2 (April 1922): 248–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/2187716.

Hezel, Francis X. ‘A Yankee Trader in Yap: Crayton Philo Holcomb’. The Journal of Pacific History, Micronesian Seminar, 10, no. 1 (January 1975): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223347508572262.

Hughes, Charles Evans, and K . Shidehara. ‘Treaty Between the United States and Japan with Regard to the Former German Islands in the Pacific Ocean, in Particular the Island of Yap’. American Journal of International Law 16, no. S2 (April 1922): 94–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2213034.

Krause, Stefan. ‘Preserving the Enduring Knowledge of Traditional Navigation and Canoe Building in Yap, Fsm’. In Traditional Knowledge and Wisdom: Themes from the Pacific Islands, 292–305. International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region, 2015. https://www.academia.edu/29831395/Preserving_the_Enduring_Knowledge_of_Traditional_Navigation_and_Canoe_Building_in_Yap_FSM_Voyaging_and_Seascapes.

Maga, Timothy P. ‘Prelude to War? The United States, Japan, and the Yap Crisis, 1918-22’. Diplomatic History 9, no. 3 (July 1985): 215–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7709.1985.tb00533.x.

McKnight, Robert K., and Sherwood Galen Lingenfelter. ‘Yap: Political Leadership and Culture Change in an Island Society’. Ethnohistory 21, no. 3 (1974): 282. https://doi.org/10.2307/481178.

Petersen, Glenn. ‘Indigenous Island Empires: Yap and Tonga Considered’. The Journal of Pacific History 35, no. 1 (June 2000): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223340050052275.

———. ‘Yap and the Yap Empire (Micronesia)’. In The Encyclopedia of Empire, edited by Nigel Dalziel and John M MacKenzie, 1–3, 2016. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe048.

Price, Willard. ‘Mysterious Micronesia: Yap, Map, and Other Islands Under Japanese Mandate Are Museums of Primitive Man’. National Geographic, April 1936. https://nationalgeographicbackissues.com/product/national-geographic-april-1936/.

Rattan, Sumitra. ‘The Yap Controversy and Its Significance’. The Journal of Pacific History 7, no. 1 (January 1972): 124–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223347208572204.

Smith, Anita. ‘Mangyol Village, Yap: A Micronesian Social Landscape’. In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Practice, edited by Steve Brown and Cari Goetcheus, 1st ed., 323–28. London, UK: Routledge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315203119-35.

‘The Controversy Over Yap Island’. Current History 14_Part-1, no. 1 (1 April 1921): 108–26. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.1921.14P1.1.108.

Tonkinson, Robert, and David Labby. ‘The Demystification of Yap. Dialectics of Culture on a Micronesian Island’. Pacific Affairs 50, no. 4 (1977): 744. https://doi.org/10.2307/2757881.

See Also

The Yap Crisis between the United States and Japan, 1914-1922

The Yap Conflict between Germany and Spain, 1883-1885