A Brief History of Truk

Background

"A Brief History of Truk" is a portion of a standard welcome, or cover, letter that was provided to visitors and incoming employees set to arrive in Chuuk -at the time still called Truk- during the mid to late 1960s.

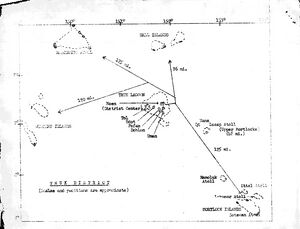

The full nine page document, which begins simply with "Greetings..." included a forward signed by Alan M. MacQuarrie, then serving as District Administrator for Truk, a part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI). No other indication is given as to specific authorship of the document, which was likely produced and printed by TTPI personnel in Chuuk. It also includes a map, as well as local contact information and logistical information of the sort needed by new arrivals.

Text of A Brief History of Truk (circa 1967)

The recorded history of Truk begins with its discovery by a Spaniard Alonso de Arellano in 1565. But this contact seems to have had no impact on either the Europeans or the Trukese, and it was not until the early nineteenth century that ships of various nationalities began to enter Truk Lagoon in any numbers. They were mostly explorers and did not markedly change the environment. However, a Frenchman, Dumont d'Urville, explored the islands rather thoroughly but, following a misunderstanding, the natives were fired upon and d’Urville escaped with his two small ships. As a consequence, when an Englishman, Andrew Cheyne visited Truk six years later he was attacked by an overwhelming Trukese force and was forced to retire. He made it widely known that the Trukese were dangerous and treacherous. So, during the short-lived whaling boom, which was over in about 1860, there were far fewer contacts between whalers and Trukese than elsewhere in the Carolines.

During Spanish rule from 1886 to 1899, the nearest administrative center was on Ponape and Truk was left alone due largely to the warlike reputation of the people. However, traders of various nationalities visited the lagoon to buy copra. Quite a few married Trukese and settled down in Truk. The chief trade item were tools and within a few years native bone and shell tools were completely replaced with iron and steel counterparts. Later the hundreds of guns introduced by the traders increased the violence of inter-island and clan warfare which had characterized the islands.

After losing Guam in the Spanish-American War, Spain sold the Northern Marianas and the Carolines to Germany in 1899. In 1903 the Germans sent an expedition to Truk and told the Trukese to turn in their guns and to cease making war. The Trukese, already tired of warefare, complied and set the pattern for acceptance of peaceful negotiation and administrative action which remains to this day, but was totally contrary to the traditional problem-solving approach.

The Germans greatly encouraged copra production which gave rise to acquisition of trade goods by the Trukese and appreciably harder work on the part of the Trukese. This era also marked the advent of corrugated iron houses. Not only was corrugated iron convenient to use but permitted the catchment of water, thus saving coconuts for copra production instead of their having to provide a beverage.

At the outbreak of World War I, Japan occupied the islands, an act that was confirmed by the League of Nations in 1920, and by the United States in 1922. Japan began pouring in capital for major developments long before any military uses for the islands were contemplated. The developments included large fishing fleets with refrigeration and drying plants for the fish, the planting of trochus beds, the cultivation of manioc, and other less successful ventures such as the introduction of pearl oysters and sponges. Under the Japanese, the steps to a money economy and dependence upon imported goods were carried far beyond the German beginning.

Meanwhile the Christian missionaries, Protestant and Catholic, were active, starting in 1885. Acceptance of Christianity was widespread and now practically complete. But Christianity has not entirely removed the fear of ghosts, although religious conversion and other changas in the Trukese way of life resulted in complete elimination of the once prestigious class of magicians who had exercised great power.

The fortification of Truk as a bastion Tor the Japanese in World War II proved disastrously inadequate. The Allied air strike against Truk in 1944 and the blockage which followed destroyed the fruits of Japanese economic development. The necessity of supporting some 35,000 Japanese and almost 10,000 Trukese off the land resulted in serious depletion of resources. Intense cultivation of sweet potatoes made unfit for use many acres of good gardening land, and the widespread use of explosives in fishing, as well as the underwater explosion of many aerial bombe and mines seriously depleted the fish population. Even today, Trukeee speak of most of the Japanese era with nostalgia but remember the war bombing and blockade as a time of extreme difficulty and hardship.

Although Moen was not as intensively fortified as Dublon, many reminders of the war remain on the landscapes largo gun emplacements with guns still intact except for the brass having been removed for sale; labyrinthine caves hollowed out of cliffs; numerous pill boxes along the beach; communication, towers and buildings; and airstrips.

When the American administration took over Truk, the District center was established on Weno (at the time called Moan).